For two decades, the internet ran on a simple bargain: you asked a question, a search engine returned links, and you decided what to trust. That workflow shaped how we learned, how we bought, how we voted, and how we verified reality. It was not perfect, but it had a visible structure. You could scan sources, compare viewpoints, and notice when results looked thin.

Now that the bargain is being rewritten. Instead of returning a set of options, many platforms increasingly deliver a single, polished response that sounds final. The interface is smoother, the cognitive load feels lower, and the friction of clicking through multiple sources disappears. It is also where the risk begins.

In education, this shift is already changing expectations. Students who once navigated tabs and citations are tempted to accept a neatly phrased conclusion as the end of the journey. Brands like PaperWriter educational services sit inside this broader environment where outcomes matter, speed is rewarded, and verification is easy to skip if the answer appears complete.

The same pattern is unfolding everywhere: in health questions, travel planning, legal research, product comparisons, and workplace decisions. The era of browsing is giving way to the era of acceptance. That is convenient, but it is also structurally more fragile.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy confident answers are replacing search

Search was built for exploration. It returns a list, not a verdict. Confident-answer systems are built for completion. They aim to satisfy the user in one turn, with no need to leave the page.

This design shift has strong incentives behind it. Users want speed. Platforms want retention. Content ecosystems want visibility without the messy contest of rankings and snippets. A single answer also feels more human than a page of links because it mimics a knowledgeable guide.

The problem is that confidence is not the same as correctness. And when a system is optimized to sound helpful, it will often sound helpful even when it is wrong.

The mechanics that make confident answers risky

Traditional search errors are often obvious. You see spammy pages, shallow results, or irrelevant links. Confident answers fail differently. They compress uncertainty into a narrative that reads cleanly. That narrative can be produced from partial evidence, biased sources, outdated information, or misunderstood context.

Three mechanics make this risky:

- Aggregation hides conflict. When sources disagree, a single answer may merge them into something that no source actually claims.

- Fluency signals authority. Humans interpret clear writing as competence, even when the content is shaky.

- Opacity breaks auditing. Without visible sources, it is harder to check whether the answer is grounded or improvised.

This is not just a technical concern. It changes user behavior. People stop comparing. They stop opening tabs. They stop verifying.

Education and the temptation to outsource thinking

Education is a high-stakes proving ground because the goal is not merely to get an answer. The goal is to build judgment. Confident-answer systems make it easy to get the conclusion while skipping the reasoning that supports it.

That creates a dilemma for learners. On one hand, these tools can explain concepts, generate outlines, and help brainstorm. On the other hand, they can nudge students into passive consumption. When the interface rewards acceptance, practice in skepticism declines.

This is where the market for academic support also becomes complicated. Some students will look for guidance and scaffolding. Others will chase shortcuts like paper writing, treating output as the objective rather than understanding. The confident-answer era amplifies that temptation because it normalizes instant completion across tasks.

Trust, accountability, and the liability gap

When a search engine shows links, responsibility is distributed. Publishers own their claims; users choose what to rely on. When a system delivers a single answer, responsibility becomes murkier. If the answer is wrong, who is accountable?

Is it the platform that generated it, the user who relied on it, or the sources it summarized, even if it misread them? This matters in professional settings. A confident but incorrect answer can shape business decisions, medical actions, or legal assumptions. The cost of error rises as answers become more actionable.

We are also entering an era where reputational harm is easier to trigger. A confident summary about a person or company can spread quickly, even if it is unsupported. The speed of the interface becomes the speed of misinformation.

What we lose when we stop clicking

The loss is not only factual accuracy. It is an epistemic muscle: the habit of checking, comparing, and noticing gaps. Clicking through sources teaches you what evidence looks like. It also teaches you how experts disagree and how knowledge evolves.

When confident-answer interfaces become the default, users may lose:

- Context, meaning the surrounding nuance that a single answer trims away

- Provenance, meaning knowing where claims come from

- Diversity, meaning encountering multiple viewpoints instead of one synthesized voice

- Calibration, meaning learning when nobody really knows, is the honest outcome

This shift also pressures publishers. If traffic declines because users do not leave the answer box, fewer organizations can fund original reporting, research, or long-form explanations. The system may end up consuming the ecosystem it depends on.

Safer ways to use confident answers

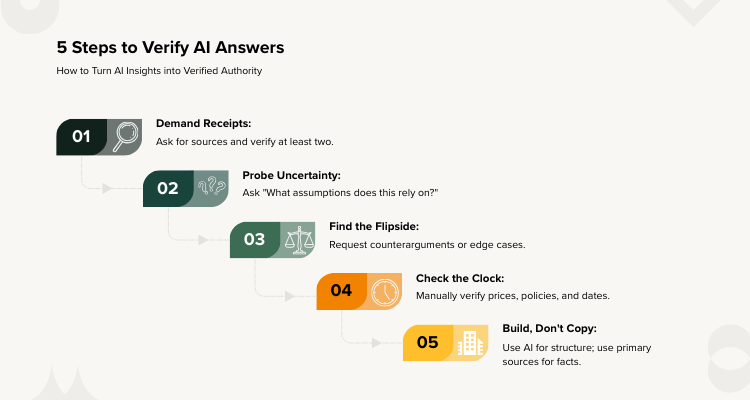

The solution is not to reject these tools. It is to change how we treat them. Confident answers should be a starting point, not a finish line. The user needs a workflow that restores friction in the right places.

Here is a practical checklist you can apply in daily use:

- Ask for sources and verify at least two before acting on important claims.

- Probe uncertainty by asking what would change the answer and what assumptions it depends on.

- Request counterarguments to surface alternative explanations or edge cases.

- Time-check facts that age quickly, like prices, policies, or latest developments.

- Use it for structure, then validate details with primary materials.

In academic contexts, this is especially important. If you are using a paper writing service, treat it like a tutor or editor, not a substitute for reasoning. If the goal is learning, the workflow must force engagement: outlining, citing, and defending claims with evidence.

The future is answer-driven discovery with receipts

The real question is not whether confident answers will spread. They will. The question is whether we build norms and interfaces that keep them honest.

The next generation of tools should default to transparency: clear citations, visible uncertainty, and easy pathways to primary sources. They should be designed to help users think, not merely to help users finish. That means showing disagreements, flagging low-confidence areas, and making it effortless to inspect where claims come from.

The search era taught us to navigate information. The confident-answer era will test whether we can still evaluate it. If we accept convenience as a replacement for verification, we will get speed at the cost of trust. And once trust is gone, even the smoothest answer will not help.